Why Don't Nurses Get Paid More?

One of the phrases you will see use again and again is that we are trying to help nurses “get paid more”. Baked into this is the assumption that nurses deserve to make more, which is pretty much true no matter how you look at it; they work really hard, doing very important work. It’s especially true considering what the last few years have been like for nurses working tough hours during a pandemic. For most people, it’s just obvious that the rewards for demanding work should be high, and few people work a job that asks for more of them than nurses.

Another way to think about it is that it’s especially bad if nurses make less money than we’d expect them to given the way job markets normally work. There are many professions that work hard, but it’s more of a problem if we see increasing demand for those workers without a similar bump in pay to reflect that. It means there’s something else happening that goes beyond wishing people were rewarded more; we are now talking about finding out why people are getting paid less than what makes sense. This is worse, and it’s something worth looking into.

The first step in trying to figure out if nurses are specifically underpaid is determining what the demand for nurses is; traditionally we’d expect standard economics to apply here and see normal supply and demand mechanics be relevant. And looking, we can see there’s was at least a pretty big shortfall of medical professionals in 2016:

America’s 3 million nurses make up the largest segment of the health-care workforce in the U.S., and nursing is currently one of the fastest-growing occupations in the country. Despite that growth, demand is outpacing supply. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1.2 million vacancies will emerge for registered nurses between 2014 and 2022.* By 2025, the shortfall is expected to be “more than twice as large as any nurse shortage experienced since the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid in the mid-1960s,” a team of Vanderbilt University nursing researchers wrote in a 2009 paper on the issue.

In that quote we see not only that a shortfall existed, but that it was expected to continue getting worse in a way that, pay aside, represented a serious problem. We can see that pattern of stagnation continuing into 2019, where nurse pay actually went down overall:

This was before the emergence of COVID-19, which we’d expect to make that demand go up. Looking at the situation on the ground, it’s apparent this happened:

Health field leaders have been warning for years that hospitals face a nursing shortage. One widely cited study projects a shortfall of 510,394 registered nurses by 2030. The main reasons, according to such groups as the American Nurses Association, are waves of baby boomer nurses entering retirement age, an aging population that will require more medical care (and more doctors and nurses), faculty shortages that limit the capacity of nursing schools to accept more students, and more nurses moving away from direct patient care or leaving the health field altogether because of stress.

COVID-19 has intensified some of those conditions. The first surges last year compelled many nurses and other health care workers to leave their jobs, but the vast majority battled through the exhaustion, despair, and fear out of a sense of duty and with faith that medical researchers would find ways to combat the disease. They just had to hang on until then.

In almost any profession, you’d expect wages to go up in a time of extreme demand for skilled and difficult-to-replace labor, especially if they were working in a role that’s emotionally and physically demanding even at the best of times. And nursing pay did go up somewhat during this period, but not nearly as much as you’d expect. This article treats 4-7% increases as massive, but they really aren’t, especially after years of tiny or non-existent pay increases.

As the last linked article notes, the pay increases nurses have seen during the pandemic haven’t stemmed turnover, which is how the labor side of a labor market makes known they just aren’t enough. That’s bad for nurses, but it’s also bad for the rest of us; we can’t just “do without” medical care because we aren’t willing to pay what it takes to keep people in an often punishing industry.

There are multiple causes that at least theoretically can cause pay increases to fail to materialize even in times of great demand. One is if the work in demand simply doesn’t create enough value; people are only willing to pay so much relative to what is being delivered. But here, nurses very literally deliver life; the cost of medical care, which is not exactly low, reflects this. The cost of health care premiums went up about 37% between 2015 and 2020, but nursing wages didn’t come close to keeping up with the same increase.

If the work creates value and demand is going up, you have to look for different reasons pay hasn’t kept pace. The first area you’d want to look at is situations that mimic the effects of oligarchies, or competing companies working with each other to keep pay levels down. But nursing is a large and diverse enough field that this would be really hard to pull off; oligarchies usually only work to depress pay if there’s just a few, large players in an industry. Healthcare has thousands.

When faced with a difficult-to-solve problem, Clipboard Health’s first move is usually to run an experiment. In this case, the experiment we ran is pretty big: it represents the entire history of our company. What Clipboard’s product does at the most fundamental level is to allow nurses much more control over their work. This includes when they work and where they work, but most relevantly how much they work for; if a shift goes up in our app with a wage lower than the actual worth of a nurse’s time, it would go unfilled. Here, nurses only work when the pay is high enough to justify what they are worth.

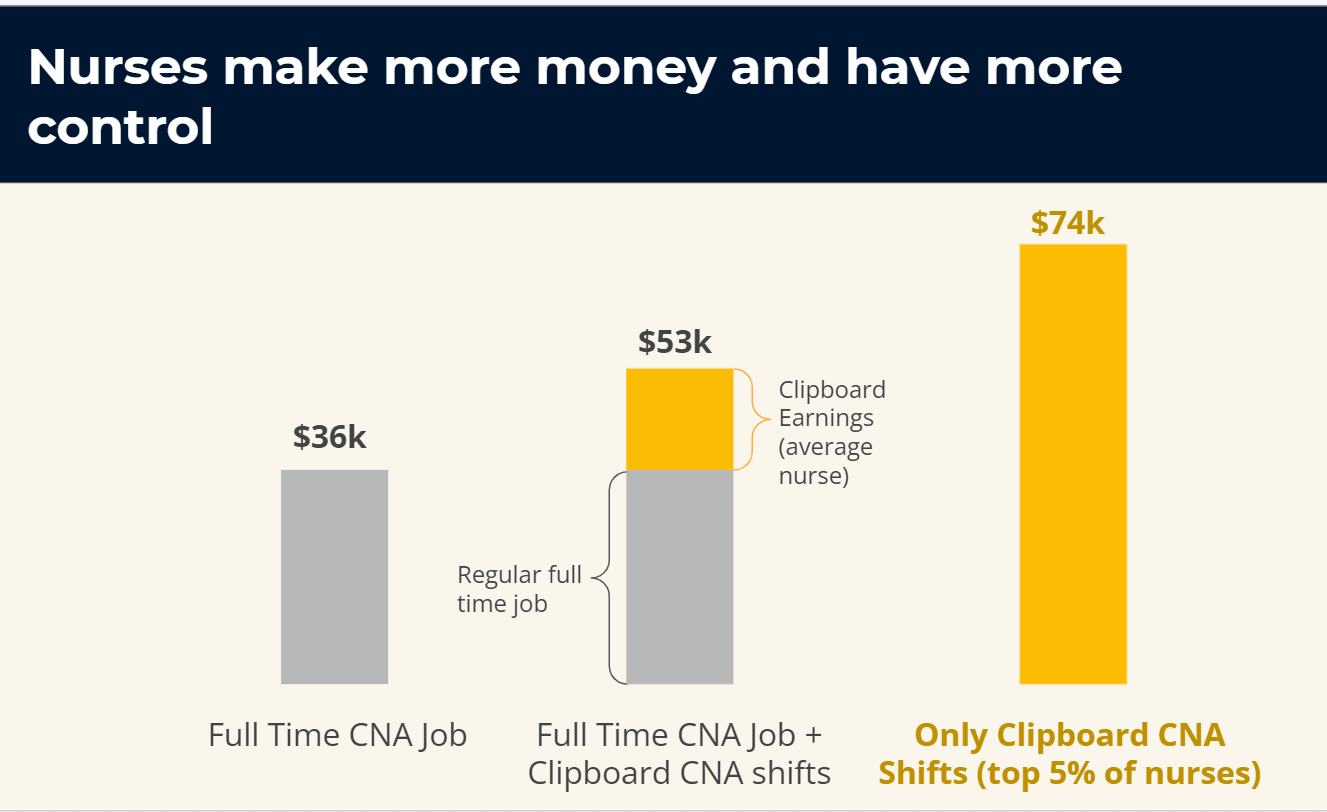

The results of the experiment are telling. When nurses find all of their work through Clipboard, they make more; often very significantly more. It’s not unusual for us to see someone making much more than what’s typical for a nurse with their qualifications in their area.

That’s a huge difference, and it validates the idea that nurses really are making more than what they are getting. More importantly, it helps to show that this isn’t because they aren’t in demand or don’t create value; when nurses have a good, high-leverage way to negotiate their wages, those same wages skyrocket.

None of this means that an oligarchy is in play, or even that anyone is doing anything intentionally wrong when determining nursing pay at healthcare facilities. But certainly something is going on that depresses nurse pay; whether that’s intentional or unintentional, it’s something that should be fixed.

We’ve made a lot of headway into that problem; it’s what we spend our time on. There’s certainly a long way to go before we’ve got the problem completely licked, but we look forward to the day when the value nurses give is perfectly balanced with the value they get back. The only way to solve a labor shortage is to make it worth it for the laborers; if we can contribute to that, we consider our time very, very well spent.

If this article is the kind of thinking you find cool or exciting, we’d love to talk to you. Apply here, and we will be in touch soon!